Amazon is a global eCommerce giant, yet even it can fail. Amazon took on the challenge of entering China, a market dominated by JD.com and Alibaba. However, its ambitious plans soon faced difficulties, and by 2019, Amazon had to shut down its Chinese marketplace.

This failure highlights the complexities of operating in China's fiercely competitive eCommerce landscape. It also offers valuable insights into Amazon’s global strategy and the unique challenges of expanding into foreign markets.

Beginnings of Chinese eCommerce

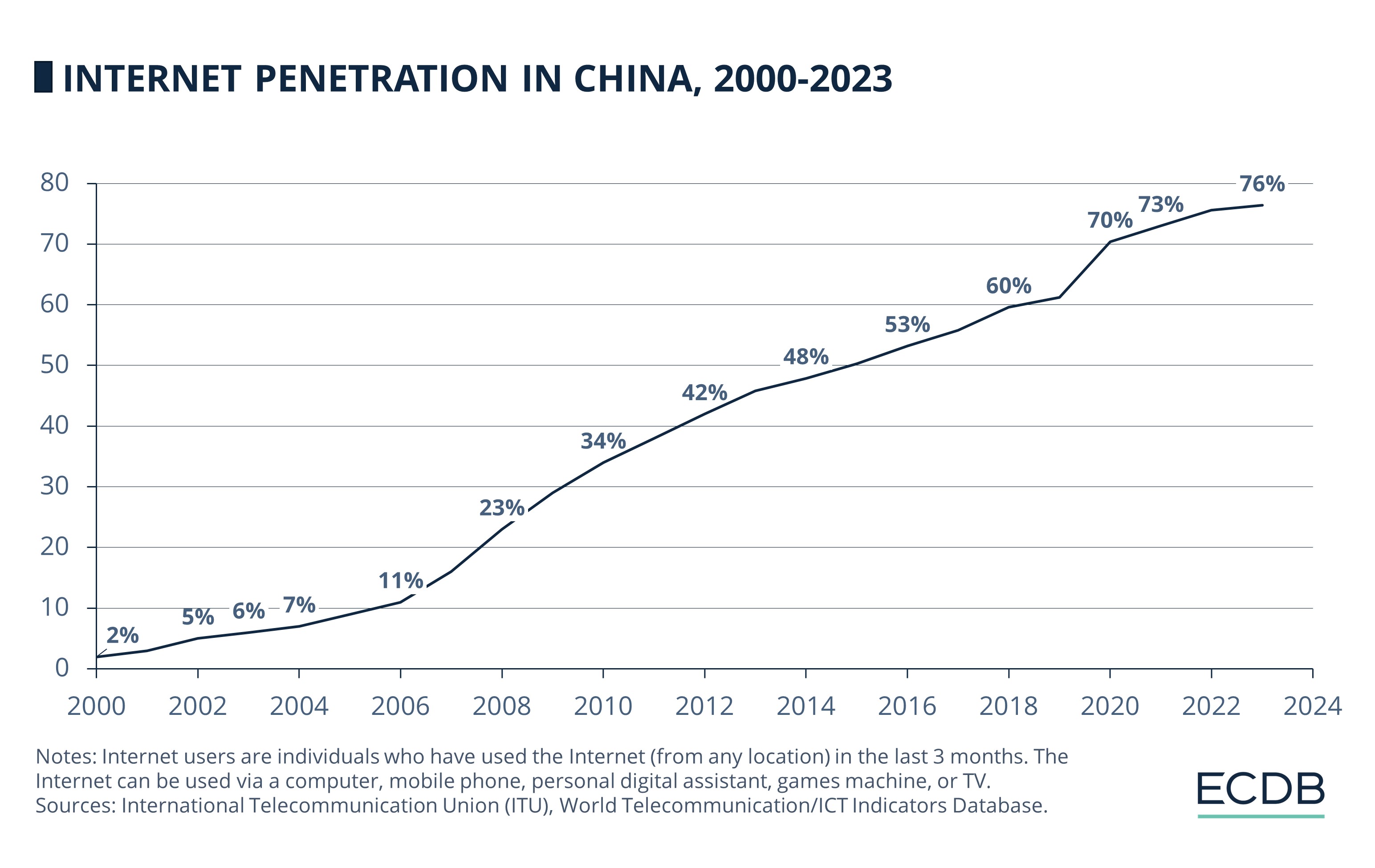

In the embryonic stage of China's eCommerce sector, roughly between 1997 and 1998, IT vendors and media companies were at the forefront, shaping the nascent market. However, a noticeable pivot occurred between 1999 and 2000 as eCommerce platforms began to emerge as the principal entities driving the adoption of online shopping. By 2001, these platforms had leveraged mass internet adoption to gain significant market control, marking a decisive shift in the industry landscape.

Much like COVID-19, the SARS epidemic of 2002-2003 acted as an unexpected catalyst for the development of consumer-facing eCommerce in China. Prior to the health crisis, JD had a single physical electronics store in Beijing, while Alibaba operated a modest B2B platform focused on wholesale trading.

The widespread lockdowns triggered by the epidemic forced these companies to innovate. JD started taking orders via phone and e-mail, laying the foundation for its future online platform, which was officially launched in 2004. Similarly, Alibaba responded by introducing Taobao, a platform aimed at connecting individual sellers with retail consumers.

The year 2004 was pivotal for another reason: the Chinese government, recognizing the sector's burgeoning potential, enacted the Electronic Signature Law to provide a legal framework for online transactions. This move added another layer of legitimacy to the rapidly evolving market.

That same year, Amazon entered the Chinese market by acquiring Joyo.com for US$75 million. Lured by the growing middle class, Amazon aimed to extend its global reach. However, it quickly discovered that navigating the complexities of the Chinese eCommerce market would be anything but straightforward.

Strategy Differences Between

Alibaba and JD.com

In the backdrop of China's rapid economic growth following its 2001 accession to the World Trade Organization, both JD and Alibaba initially aimed their eCommerce services at residents in China's affluent coastal cities. However, these consumers, despite benefiting from the country's economic surge, remained relatively price-sensitive.

Alibaba sought to cater to these preferences by expanding its nascent Taobao platform to include a range of low-value, low-quality items, focusing on daily essentials and fast-moving consumer goods. This pricing strategy was driven by the competitive nature of online pricing and the ability of many Taobao sellers to source products directly from factories, thereby avoiding middlemen.

To bolster consumer trust in the emerging platform, Alibaba introduced Alipay in 2004. This escrow service held customer payments and released them to sellers only after buyers confirmed receipt of their orders. Originally intended to complement Alibaba's eCommerce operations, Alipay would later become a cornerstone of the separate financial services entity, Ant Group.

In contrast to Alibaba's focus on scale and price competitiveness, JD remained committed to its original business model of providing authentic, high-quality electronics. This specialization presented unique challenges, particularly when it came to shipping delicate and high-value items. The company encountered frequent problems with third-party couriers damaging goods during delivery, prompting JD to create its own logistics arm. While this move led to higher prices, it was in line with JD's emphasis on premium service and quality.

Chinese eCommerce: B2C vs. C2C

in Early 2000s

In the initial years of China's eCommerce sector, the focus was sharply divided between B2C (business-to-consumer) and C2C (consumer-to-consumer) models.

Taobao emerged as the dominant C2C platform, while Amazon.cn and 360buy, now JD.com, specialized in B2C, targeting specific verticals like books and electronics. Concurrently, traditional retailers like Suning extended their business models to include online sales, mitigating the online sector's disruptive impact.

This dual focus between B2C and C2C became a defining feature of China's burgeoning eCommerce market. Platforms like Taobao catered to different consumer preferences compared to B2C entities like Amazon.cn. The variance in business models and target demographics shaped the competitive dynamics of the industry's early players, setting the course for their future adaptation to evolving market conditions.

Chinese eCommerce Sector

Becomes Competitive

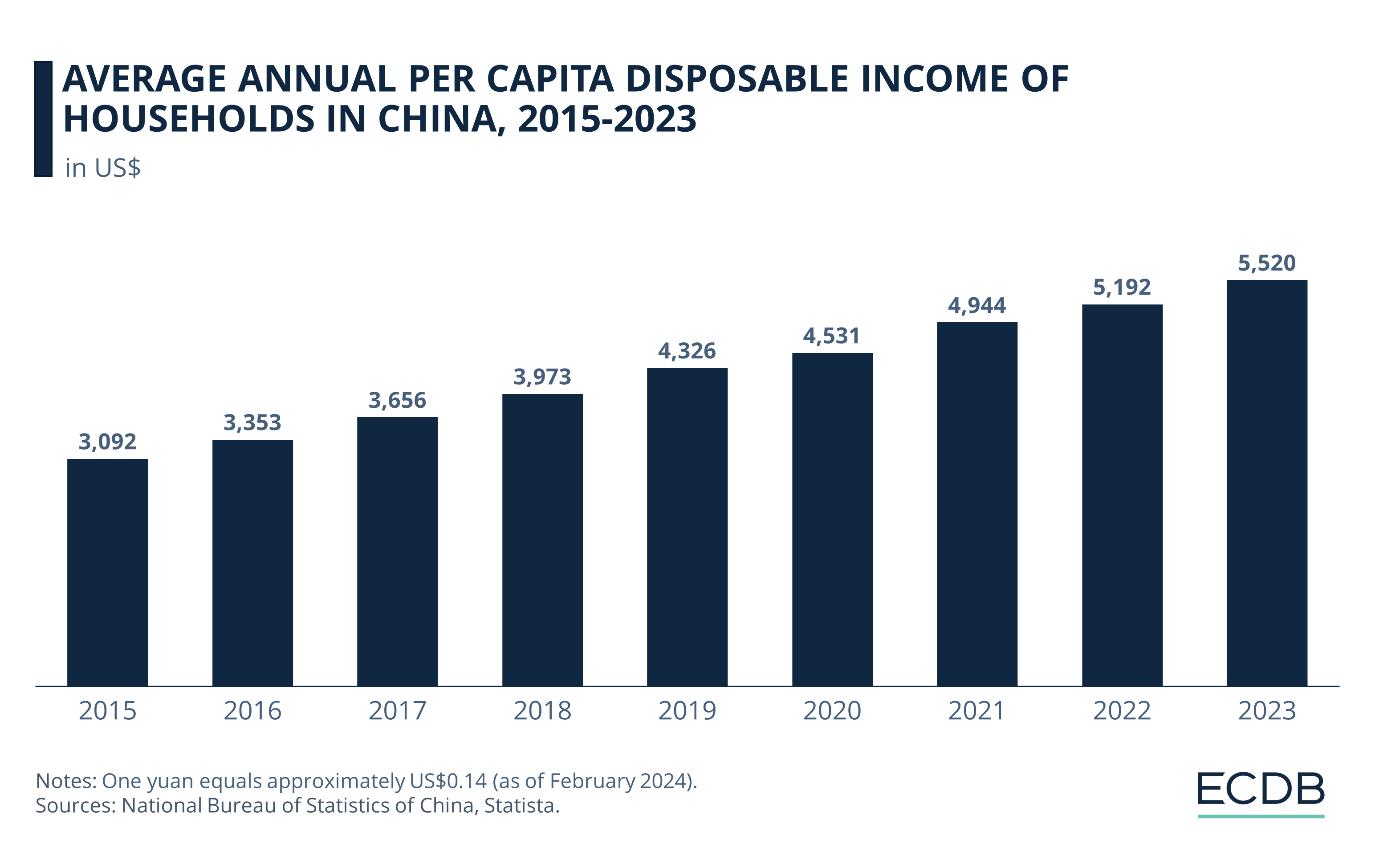

As China's middle class matured, amassing more wealth and displaying evolved consumer preferences, the country's eCommerce environment underwent transformative changes to meet these new demands.

Alibaba astutely launched T-Mall in 2008 to focus on higher-quality, branded products. By the first quarter of 2008, its customer-to-customer (C2C) platform, Taobao, had a commanding 83.8% market share, dwarfing competitors PaiPai and TOM Eachnet.

Alibaba further broadened its eCommerce scope through Alibaba.com, its business-to-business (B2B) portal, and gained more influence via a 2005 agreement with Yahoo Inc. Taobao's transaction volume reached US$6.23 billion in 2007, with 67.3% of its users shopping exclusively on its platform.

As the eCommerce space matured towards the end of the decade, Alibaba and JD.com strengthened their positions, setting a highly competitive bar for international entrants like Amazon. In the B2C sector, Dangdang and Amazon's Chinese entity, Joyo, continued to be fierce competitors.

However, Taobao wasn't without challenges; it ranked third in brand reliability among major platforms. TOM Eachnet, despite high brand awareness, had a low 20.1% conversion rate. The entry of Baidu.com, China's leading search engine, also increased competition.

Amazon in China: Rebranding Efforts

When Amazon acquired Joyo.com in 2004 for US$75 million, the expectation was that the tech behemoth would leverage its global scale to become a dominant player in China. That aim, however, was marred by the rise of formidable local competitors.

Alibaba's Taobao and JD.com entered the eCommerce arena around the same time as Amazon's acquisition, setting the stage for a clash of titans that Amazon would ultimately lose.

In an effort to better align its Chinese unit with its global operations, Amazon underwent a rebranding campaign in 2011 and renamed itself as “Amazon China”. Up until that point, the U.S. retail giant had operated under the hybrid name "Joyo Amazon".

In addition to the name change, Amazon took the step of streamlining its web presence in China. The company directed the abbreviated URL “z.cn” to its existing Amazon China homepage, hosted at “amazon.cn”. This shorter URL was easier to remember and access, part of a broader strategy to make the platform more user-friendly for Chinese consumers.

Despite ambitious rebranding efforts and a slew of initiatives aimed at capturing the Chinese consumer, Amazon found itself unable to surpass, or even closely compete with, local powerhouses Alibaba Group and JD.com.

Amazon initially seemed to make inroads, but that success was short-lived. In 2008, Amazon China held 15.4% of the country's eCommerce market share. However, by 2015, that figure had dwindled to just 1.1%. Data for the first quarter of 2015 shows that T-Mall dominated with a 58.6% share, followed by Jingdong at 22.8%, Vipshop at 3.8%, and Suning at 2.8%. During this period, Amazon's operations in China registered annual losses exceeding US$600 million.

Amazon Struggles in China

In the mid-2010s, Amazon was still in an uphill battle in the Chinese eCommerce sector. Dominated by local giants Alibaba and JD.com, Amazon took strategic steps to bolster its presence in China, albeit with measured success.

In 2014, Amazon embarked on a calculated move to enhance its operational footprint in China by setting up a logistics warehouse in Shanghai’s new free-trade zone. The impetus behind this decision was to gain a competitive advantage in shipping and cost structure, aiming to elevate its marginal share of China's online shopping market. Amazon sought to capitalize on the benefits of the free-trade zone to offer quicker delivery and lower shipping fees.

However, two years later in 2016, the landscape was still far from favorable for Amazon. Regulatory hurdles, like restrictions on streaming video and music—central features for Amazon’s Prime service in the U.S.—placed the company at a disadvantage. Amazon’s growth was also constrained by Alibaba and JD.com, which not only commanded significant market share but also adeptly navigated the local regulations that stifled foreign entrants.

Notably, Amazon's struggle in China contrasted with its aggressive expansion in the U.S., exposing a difference in operational tempo between the two markets. Alibaba's ventures in the U.S. also encountered obstacles, illuminating that while the two companies are often compared as rivals, their core business models diverge—Alibaba operates primarily as a marketplace, whereas Amazon acts mainly as a seller.

Avenues of Modest Success

While Amazon's primary retail operations encountered challenges in China, the firm carved out gains in alternative sectors such as cloud services and Kindle e-readers.

In a move designed to resonate with local consumers, Amazon launched a customized Kindle e-reader in 2017. The device granted access not only to Amazon's expansive digital library but also to Migu, a local e-book outlet operated by the state-owned China Mobile. Sweetening the deal, the e-reader included a one-year subscription to Amazon Prime's complimentary shipping services. Yet, even these forays into the Chinese consumer realm were tempered by regulatory limitations set forth by Beijing, which curtailed the ventures' growth prospects.

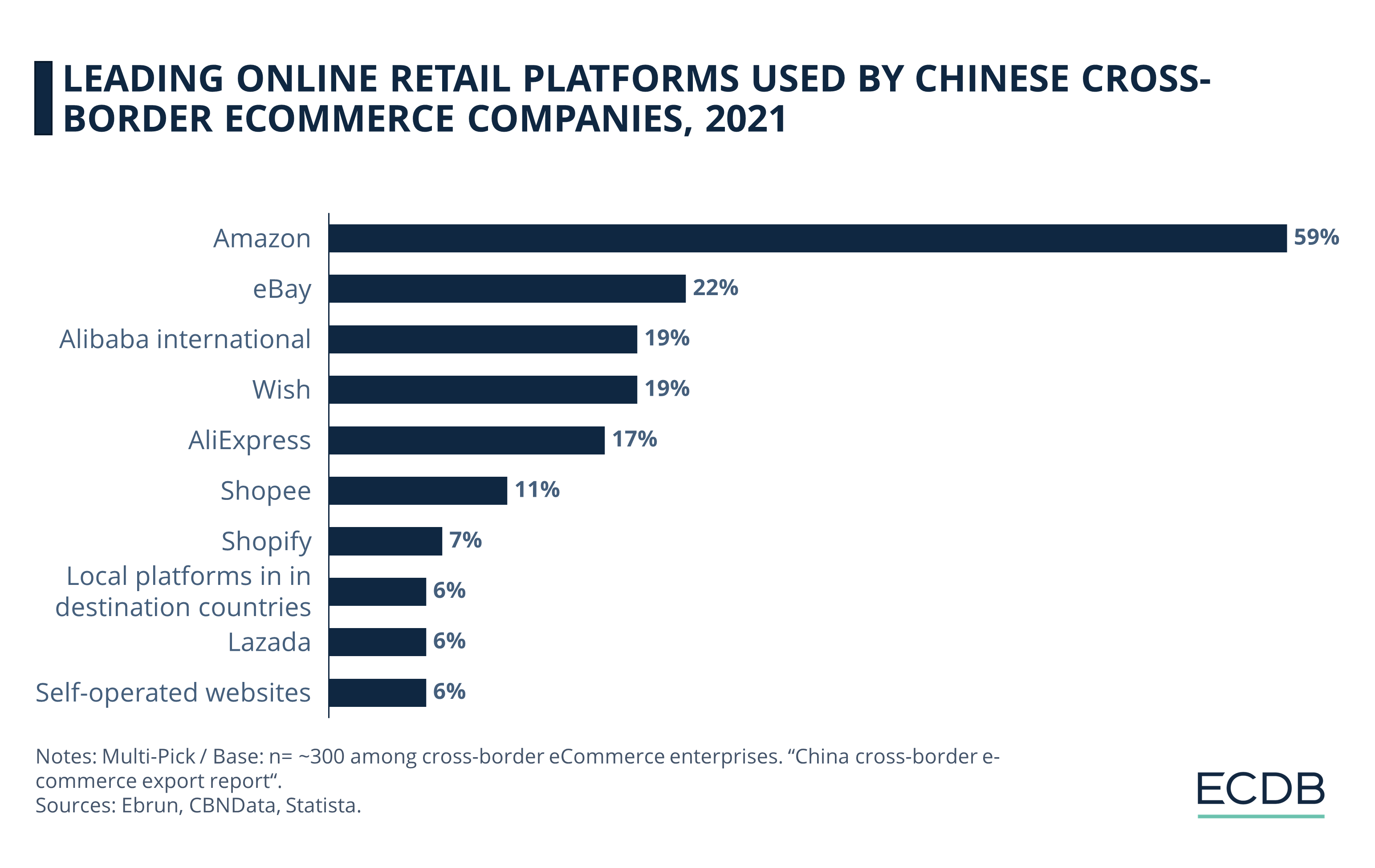

On another front, Amazon achieved considerable success in the realm of cross-border online commerce. A study from 2016 disclosed that 62% of Chinese sellers favored Amazon for conducting their transactions, outpacing even Alibaba's AliExpress, also highlighting Amazon's influential role in global eCommerce activities involving China-based sellers, even as it grappled with headwinds in its efforts to crack the domestic retail sector.

Regulatory Challenges for

Amazon in China

While Amazon managed to leverage its strength in cross-border eCommerce and create offerings tailored to local tastes, it found itself navigating a complex and shifting regulatory landscape. This increasingly stringent environment posed challenges not just to its specialized sectors, but to its very business model within China's borders.

Among many other examples, in 2017, the tightening regulatory environment in China forced Amazon into a strategic retrenchment. Beijing Sinnet Technology Co Ltd, Amazon's local partner, acquired the hardware of Amazon Web Services (AWS) in China, which was not an elective business move, but a compliance necessity. That year, China's laws mandated companies to store data locally. While AWS could retain intellectual property rights for its services on a global scale, it had to relinquish certain physical assets within China's borders.

Moreover, AWS also faced restrictions on offering services that could circumvent China's infamous censorship system, the Great Firewall, under direct instructions from the Chinese government. This regulatory headwind didn't just affect Amazon; it foreshadowed stringent controls that other global technology firms, including Microsoft and Oracle, would eventually face.

Amazon Admits Defeat in China

By 2019, Amazon opted for a significant strategic shift, effectively exiting China's domestic online retail arena. Financial documents from that period laid bare the company's diminishing foothold; sales in China had become so marginal they no longer merited an individual entry in financial reports. This underscored the receding importance of the Chinese market in Amazon's overall global strategy.

Yet, the company's retreat was not wholesale. Amazon stressed its continued focus on cross-border sales, citing robust demand from Chinese buyers. It also confirmed that it would maintain its Kindle and cloud computing offerings in the country. Further, Amazon pledged ongoing support for Chinese brands eager to connect with consumers in the U.S. and other international markets.

The company's retraction in China was emblematic of a broader trend: U.S. tech firms increasingly find the Chinese market elusive. This stands in stark contrast to American retailers like Walmart, which have successfully partnered with local Chinese entities such as JD.com, gaining a more effective reach into China's consumer base.

As a result of its China experiences, Amazon has redirected its energies, notably committing a formidable US$5.5 billion to expansion efforts in India—a market it deems more conducive to long-term success. Thus, Amazon's years in China serve as an intricate lesson in the complexities of engaging a foreign market replete with agile, well-established local players.

Amazon in China: Final Thoughts

Amazon's decline in China was not merely the result of its own strategic missteps, but also reflected the strong local strategies employed by Alibaba and JD.com:

Alibaba had carved out a dominant local presence with a business model tailored to the tastes and habits of Chinese consumers, extending even into financial services. Its sheer scale was evident in its 2014 sales projections of US$420 billion, dwarfing Amazon's US$74.4 billion in fiscal 2013. JD.com similarly built a resilient platform, offering an extensive product range and efficient logistics, thereby undercutting Amazon's market impact.

In contrast, Amazon's approach in China significantly diverged from that of its local competitors. The American giant sought to duplicate its successful U.S. model by controlling a large portion of its own inventory and constructing its own delivery network. This centralized model, however, failed to cater to the specific expectations of Chinese consumers.

Alibaba took a more flexible route, positioning itself as a platform for a host of smaller vendors, thereby offering a broader range of products without the necessity of managing extensive inventory. It also utilized local delivery services, enabling more competitive pricing.

Over time, Alibaba's adaptive, localized model emerged as far more effective in the Chinese market. While Amazon's inventory-centric strategy may have found success in other markets, it lacked the agility needed to thrive in a Chinese retail ecosystem dominated by adaptable, localized approaches.

The contrast in strategies underlines why Alibaba and JD.com managed to significantly outperform Amazon in China.